We’ll cover each region in weekly previews, describing the available army lists, talking about their evolution and the weapons and tactics they employ.

Japan and its clans

Japan in the 16th century was a politically fractured reality: the Sengoku Jidai period (Warring States Era) was a period of civil war in Japan from 1467 to 1600. During that time, the Emperor of Japan was only a religious and ceremonial figure who delegated power to the Shōgun, the military governor of Japan. The era began with the Ōnin War (1467-1477) where a dispute between potential heirs to the Ashikaga Shogunate led to a civil war involving several daimyō and the destruction of Kyoto. Since then, the authority of the Shogunate had diminished while the daimyo increased their authority over their fiefs and fought against each other to expand their realms.

The era brought about the rise and fall of several prominent clans. Old families like the Imagawa and Hōjō would be eliminated. Some families would break away from their old masters and forge a path of their own, like the Tokugawa. The Takeda family, hailing from an agriculturally poor province, dominated central Japan through exploitation of their gold mines, and employed cunning military and political strategies against their neighbours. Peasants could become lords and make a name for themselves, like the Toyotomi.

An Oda army defending behind field fortifications against the Takeda

The armies of the Sengoku Jidai were manifestations of the feudal social structure of Japan, which revolved around kinsmen and vassals. The head of the clan and its army was the daimyō, literally translated as “great name”. He was supported by the kashindan. These were a group of blood relatives and retainers associated by family ties, marriage, filial oaths, and hereditary vassalage.

A standing army was uncommon but was popularised during the later years of the Sengoku Jidai. For the majority of the period, armies were composed of farmers who needed to stand down during the planting and harvesting seasons.

Typically, when a call to arms was issued, each landowning samurai was required to muster a pre-determined quantity of troops and equipment based on his wealth. Troops from all around the province would then converge at a designated place where they would be reorganised into battalions wielding similar weaponry and start practicing drills. The daimyō determined the chain of command for the campaign. The prominent retainers would act as bushō (general). A taishō (field marshal, commander-in-chief) would be appointed if the daimyō did not intend to take the role himself.

Each general commanded a division comprised of specialised battalions of cavalry, missile and melee troops mustered from their fiefs. These troops were only loyal to their direct lord and the daimyo, not the taishō or other generals. To reflect this, Japanese commanders who are not assigned as the Commander-in-Chief are classified as Ally-Generals. Their units cannot receive any command effects from other generals except the C-in-C.

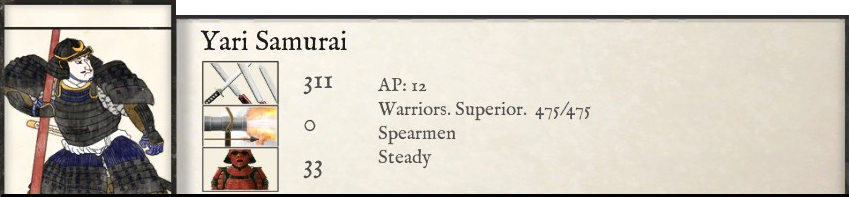

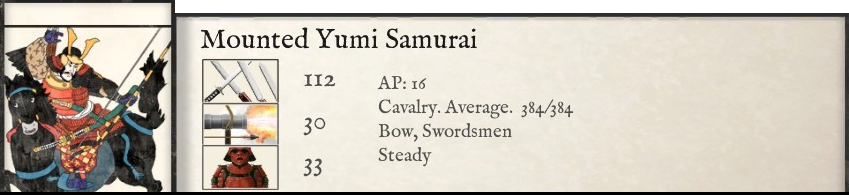

The Japanese wielded a variety of weapons, the prominent ones being the katana (sword), yari (spear), naginata (polearm), yumi (bow) and teppō (matchlock). Contrary to popular depictions, the katana was just a sidearm and the yari was the weapon of choice due to its range and versatility. All classes of soldier, from the lowly ashigaru to the elite samurai, wore armour of lamellar construction.

Before 1530, mounted samurai would primarily use bows, similar to other East Asian cavalry. The switch to the yari and shock tactics happened around the 1530s, pioneered by the Takeda clan.

The main fighting force was foot samurai, augmented by ashigaru. Due to the rugged terrain, the Japanese utilised loose formations and fighting was done man-to-man, as depicted in martial arts and samurai films. Hence they are classified as Warriors.

In 1543, Portuguese merchants introduced matchlock firearms (teppō) to the Japanese. Teppō ashigaru infantry were deployed, but there weren’t enough firearms available to equip large units. These small units are classified as Light Foot and are primarily used as skirmish troops.

By 1551, as battles grew larger, more and more ashigaru infantry were being mustered, as a result of which the proportion of foot samurai in the army was somewhat reduced. The Battle of Nagashino in 1575 showed the Japanese that massed volley fire from firearms behind field defences could defeat samurai cavalry. From then on, teppō ashigaru formations were larger and did not engage in mere skirmishing tactics.

By 1577, samurai cavalry had lost its appeal due to changes in battlefield technology and tactics. And by 1592, ashigaru infantry tactics evolved into fighting in close formation. They would receive better training and form the backbone of the Late Sengoku Era army. Ashigaru infantry, including yumi and teppō armed units, are now classified as Medium Foot. A century of fighting also depleted the numbers of available samurai. Just like their mounted counterparts, foot samurai, who still fought man-to-man, were finding it harder to dominate the battlefield against organized peasant foot troops. The 1590s also introduced some other elements of modern warfare such as light artillery, but these were not used as extensively as on the Asian mainland.

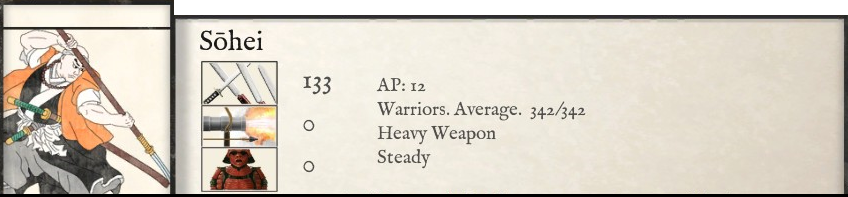

Warrior-monks

Buddhist monks of various temples also trained for combat. They had to take up arms in order to protect their temples from rival sects. These warrior monks were called sōhei. During the Gempei War (1180-1185), the sōhei eventually became embroiled in secular politics as they joined the lords that supported their temple. This was repeated during the Sengoku Jidai and the daimyō were able to gain the support of sōhei from their local temples.

The monks’ weapon of choice was the naginata, a long-bladed polearm. They also used bows and matchlocks. Occasionally, they can be seen wearing armour underneath their robes but the majority were unarmoured.

Ikkō-ikki

Alongside the various japanese clans, you can also lead a different type of army which finds its origin in feudal Japan: the Ikkō-ikki. It was a militant movement which followed the beliefs of the Jōdo Shinshū (True Pure Land) sect of Buddhism which taught that all believers are equally saved by Amida Buddha's grace.

The Ikkō-ikki revolution gave some sōhei a new purpose. Instead of fighting for their temples and patrons, they fought under an ideology of equality and independence from the daimyō. Ikkō-ikki rebel armies were mostly made up of sōhei and supported by armed peasant mobs. Samurai who shared their ideals also joined but did not form separate units. The samurai fought alongside the monks and peasants and provided leadership as well as training.