MING CHINESE LIST IDEAS:

Post 1: Intro and tactical and list notes

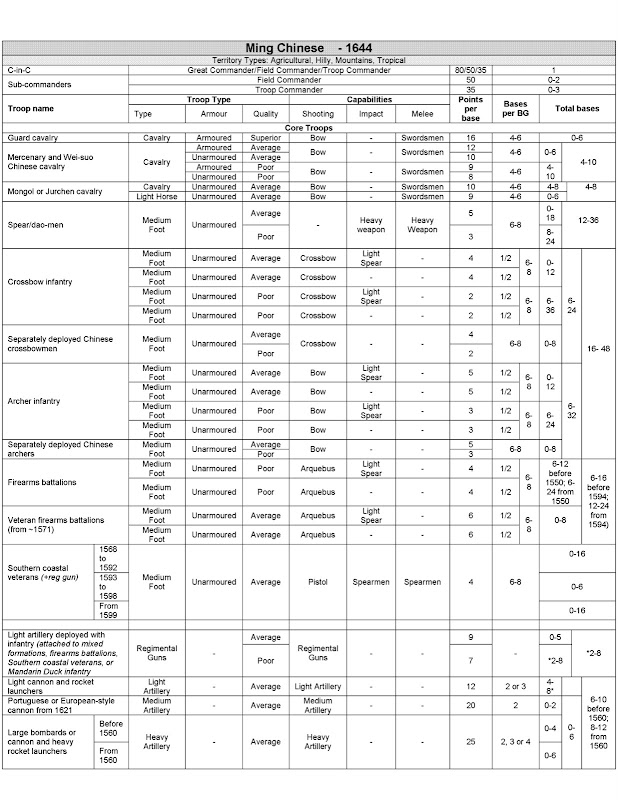

Post 2: Draft List

Post 3: Other notes - playtest, armour/appearance/FOGAM transition

(This part is not polished and not entirely finished, especially special campaign notes, but the substance is here. It is a mix of American and British English at this point.)

Although in this period the Ming fought on average more than one substantial military campaign per year, mostly suppressing rebels or acting against northern tribesmen, and although its economy and population continued to grow, the dynasty was past its prime militarily. The Tumu disaster of 1449 shattered Chinese prestige, and the dynasty (except for a modest revival under the Wanli emperor in the late 16th century) shifted from expansion of its tributary vassal system and a vigorous forward policy of “awesomeness” against the Mongols (evidenced by the confident relocation of the capital early in the dynasty from Nanjing to the rebuilt city of Beijing near the frontier, and regular deep strikes to bring war home to the Mongols) to an introverted defensive posture that turned bases meant for offensive expeditions into a defensive network of forts, walls, and garrisons that was understrength and permeable to raiders.

The Ming bureaucracy focused on order, control, and stability under the Confucian system. The military and war and the military were distasteful, socially inferior, disorderly, disruptive and destabilizing – the more successful a general, the greater the threat. They were routinely second-guessed, overruled, censured and punished as part of the political process, which fostered cautious, face-saving and irresolute generalship. The Ming founder had settled troops through the country under a hereditary militia system (Wei-suo) intended to provide the dynasty with a self-supporting trained army and officer corps. Training camps in infantry, cavalry and artillery combat skills were established, but fell into disuse. The system was characterized by neglect, abuse, extortion of troops by officers, misappropriation of resources by officials and officers, and expenditure bloated by routine peculation and other forms of corruption. The strength of the Chinese bureaucracy ensured that periodic reforms were no more than ripples in a stagnant pool.

From the early years of the system, troops were used for non-military tasks, including construction, transportation, and personal service to officers and officials. This ruined the fighting ability of the troops. In our period the wei-suo troops were in general ill-equipped, undisciplined, untrained, and unwilling to fight, though ready to riot. Circa 1600 a Jesuit described the hereditary army as “an expensive rabble” of incompetents, and both Chinese and Europeans were critical of the army. Theoretical strength reached 3 – 4 million in the late dynasty, but only roughly 20% of this was real and only part of that battleworthy. Availability of troops for action was also hindered by local officials and officers who sought to hold on to troops for defense and their own projects.

The decline reached a low point in the mid-1500s. When Mongol raiders reached Beijing in the 1550s the nominal strength of the troops in the city was 107,000 but the government had a hard time raising 50,000 men from wide-ranging garrisons. Barely 30,000 cavalry could be raised against the Mongols, and an army of 60,000 raised to face the attack on Beijing by Altan Khan in 1550 fled rather than face them outside the walls. As a result, mercenaries were routinely hired for active campaigning, Ming southern troops tended to be polearm infantry. Northern troops tended to be horse archers with short swords. Other than barbarian tribesmen from the south in both the Ming and Qing dynasties, the infantry was almost entirely Han Chinese, often poor peasants, bandits, or the dregs of society, and by this time was trained to and most suitable for defending walls and fortified positions rather than taking the offensive in the open field. Most non-Han soldiers in Chinese armies were horse-riding nomads; in the field army cavalry was largely Mongol or Jurchen. Native Chinese cavalry was variable in quality and sometimes no more than mounted infantry, their numbers constrained by the often limited number of horses available to China (which varied with its influence over neighboring nomad regions).

Regulations provided that an array of flags, gongs and drums be used to convey orders, but the actual conduct of battle is described in Osprey’s Late Imperial Chinese Armies thus: "On the battlefield itself, rather than trying to manoeuvre these huge and sketchily trained masses, generals tended to put themselves at the head of specially picked units of not much more than battalion size and use these to spearhead attacks. Liu T’ing, for example, led a bodyguard of 736 men in 1619, fighting personally in the front rank with a two-handed sword. Many such elite troops were ferocious fighters who took vows to die with their commanders rather than flee, and their desperate charges greatly impressed their allies in Korea. However, with most of the able officers fighting as ordinary soldiers, the problems of control became even worse; the tactical manoeuvre warfare practiced by earlier Ming armies had become largely replaced by a reliance on massed frontal assaults".

Other than the final struggle against the Manchu, the only foreign war against a modern opponent was against Japan in aid of Ming’s Korean vassal from 1592-1598 (the “Imjin War”). The strength committed in the first campaign was approximately 50,000 men. Ray Huang has estimated the combined strength of the Ming army and navy committed at the height of the second campaign at 75,000 men. Among these were the best Imperial troops and generals. Having started with a low opinion of the other’s military effectiveness, the Chinese and Japanese were both surprised by the strengths of the other. The Koreans and Chinese were shocked by the Japanese infantry’s withering firepower, the Japanese by the Chinese artillery. The Japanese relied even more heavily on their teppō (matchlocks) and the Chinese reinforced their gunpowder arms and rotated in additional southern troops (these were trained in the tactics first devised by the famed Ming commander Qi Jiguang (1528-88) to combat the Wo-k’ou pirates on the southeast China coast).

At the same time, the Wanli emperor was involved in suppressing the major Ordos Mongol rebellion in the north and in a large and prolonged campaign against rebels under the formerly semi-autonomous Yang Yinlong in Sichuan from 1587-1600. The Imjin War helped preserve Korea, but the costs in trained manpower and silver of all these campaigns were large. Ming military vigour flagged after 1600, partly due to these costly campaigns, while at the same time the unified Jurchen peoples were forming an expansionist Manchu state. Some armies drew troops from across the empire, and the Korea expedition included small vassal contingents (to help overawe the enemy with the extent of Ming power).

The economic boom from trade with European powers in the 16th century flagged in the 1620s and 1640s, which hurt the Ming. The Manchu pushed the border west with a combination of bribery and force, and ultimately seized the Imperial throne in 1644 as the Qing dynasty, aided by Ming internal turmoil and defections, including the capable commander Wu Sangui of the last field army in the north, which fought well against the Manchus and then the Shun rebels. The last Ming claimant to the throne was defeated in 1662. Three Ming commanders in the south operating semi-autonomously under the Manchu dynasty revolted in the 1670s.

TACTICAL AND LIST NOTES:

The Chinese did not share the Western ideals of the universal soldier or grouping troops of the same kind together with the same weapons. Chinese organization and tactics sought combined arms benefits within as well as between units, although the specific mix was based on resources and opponent types. Mixing missile foot and close combat foot (such as spearmen and shielded swordsmen) in different ranks within tactical units was a continuation of traditional practice with the addition of gunpowder weapons. Typical would be at least one rank of spear/dao men available to form a first rank in front of the shooters to provide steadiness and resist a charge.

The most distinguished and best known general of the late Ming dynasty was Qi Jiguang (1528-1588) (aka Ch'i Chi-kuang), a hereditary officer on active service from 1544 to 1585. He was a top administrator, organizer, military engineer, manual writer, and field commander, with enough political skills in compromise to achieve some positive results within the restraints of the Ming system thanks to top-level bureaucratic patronage from Senior Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng based on his successes. His military manuals were republished into the 19th century, and were the prime reference for the Korean military reorganization starting in late 1593.

Training (such as there was) and tactics at the Ming’s few military training schools focused on military classics for officers and individual combat skills for troops, rather than drill or battle management. Commanders who bothered to drill troops were rare. An important exception was General Qi Jiguang, who between 1556 and 1582 successfully carried the internal combined arms approach down to drilled and disciplined coordination of different troop types at squad level in the famous Mandarin Duck formation, designed initially to counter Wo-k’ou pirate swordsmen/archers and later Mongol cavalry. Political obstacles to reforms prevented broad adoption of his ideas during his lifetime, but his manuals became classics and Qi’s reforms endured in Zhejiang province on the southern coast. Trained troops from there later proved valuable in the 1590s against the Japanese.

Guard cavalry: This is assumed to represent the best available cavalry, among them the “guard” units around Beijing, although armies in other regions, as well as rebel armies (which usually coalesced around an army core) might have these. The Beijing “guards” did not perform well against the Mongols at Tumu in 1449 and were unable to face them outside the walls of the city a century later. More than one superior BG is excessive.

Mercenary and Wei-suo Chinese cavalry:

Northern cavalry was generally better and better armoured. The minimums here are intended to force use of some Poor cavalry and limit the number of good BGs that can be fielded without resort to allies. Horses available were limited. Ming cavalry dismounted to fight in Korea when mud or lack of fighting room hindered them.

Guard cavalry and Mercenary and Wei-suo Chinese cavalry may dismount. Many were effectively mounted infantry.

Mongol or Jurchen cavalry: These are the “northern barbarians” from beyond the northern and western frontiers, often serving as mercenaries in Chinese armies. Some even settled within China, although they were victimized when there was war with the Mongols. To raise large numbers requires an allied contingent.

Mongol Allies are not available from 1644 <harder> or if fighting against the united Mongol tribes (for example, Altan Khan’s wars from 1550 to 1571 or 1582-158X[need to check end date], but not the more localized Ordos Rebellion of 1592).

Jurchen Allies are not available if fighting against the united Jurchen tribes (for example, from 1592-15XX, and [cover transition to Manchu at war with the Ming in 1600s].

Chinese spear- and dao-men:

These include troops with spears, tridents, halberds of Chinese designs, and swordsmen. It is intended that one poor BG be compulsory and that no more than 3 BGs may be Average. These are suitable troops to attack with, or to support light artillery in the attack and heavier artillery on defense. They are down a POA in Impact vs. horse archers, but do enjoy a Melee POA so the horse should break off.

Ming melee troops were equipped with sword and shield, some variant of a spear, or polearms, and were in theory equipped with chain, brigandine or lamellar armour but in practice appear to be equipped with leather or wadded cloth armour.

Different weapons served different roles in combat. Chinese armies of the Ming period used a wide variety of spears and polearms. Spears were generally quite long and tipped with a socketed, tapered steel blade. Some types had downward curving hooks projecting from the blade that were designed for dismounting horsemen. Bamboo, being sturdy and light, was commonly used. Polearms were favoured for use against Japanese swordsmen. Tridents, martial arts weapons like military rakes to unseat riders, and more exotic designs existed, but it is doubtful that they were used in large numbers in the army.

Gunpowder Empire?

The Ming was the first Chinese gunpowder dynasty, and viewed gunpowder weapons as the bulwark of their power against the surrounding barbarians. The concept and organisation of artillery as a distinct combat arm took root in China only with modernisation in the 19th century – Ming thinking viewed firearms ranging from handguns to heavy cannon as part of a continuum of weapons, and this affected how they were employed. The Ming favoured a wide variety of hand firearms, rockets and light cannon integral with the infantry. Some of these lighter artillery are treated as Regimental Guns and others by separate battle groups. With a few exceptions, medium and heavy artillery were used in assault and defence of towns, defiles (such as Chiksan, 1597) and fortified positions but not in open field battles.

In field battles the Ming favored light and very light cannon, rockets, grenades, and an ingenious variety of other gunpowder weapons and devices (as well as fortifications, wagons and portable obstacles) distributed to the units along the line of battle to bolster the firepower and capabilities of the infantry, which included a substantial portion of troops armed with a bow, crossbow, simple arquebus, handgun or fire lance (gunpowder-projected arrow). The objective was to disrupt and demoralize an attacking enemy, stopping them at or before contact and then breaking them through multiple forms of attack, including gunfire. These shooters were mixed with close combat infantry for protection against melee attack. Both northern tribesmen and southern rebels disliked facing gunfire or artillery bombardment.

While constant warfare among different states led to competitive evolution of military technology, organization and tactics in Europe, and in Japan during the Sengoku period, the conservative and xenophobic Chinese political culture faced no major symmetric threat to focus attention on refining weapons and tactics until the 1590s. The Ming did, however, take in new technologies from elsewhere to some extent.

An important fire-arm was the fire lance--essentially a spear fired from a disposable tube. It was reputed to be able to penetrate most armour and could strike down several enemies in one shot.

Exposure to Ottoman technology in 1513-1524 and to Portuguese matchlocks in the 1540s led to updating of Ming technology to produce a new niaoqian (matchlock arquebus). Matchlocks grew in number, inspired in part by experience facing the Japanese teppō in the Wo-k’uo and Imjin Wars, but Ming troops continued to include traditional fire-lances, three-eyed guns and other man-portable firearms into the 1600s. The flintlock and wheel lock became known, but there was no need to adopt them. Existing models were retained as sufficient, considerations including cost, simplicity of operation, greater suitability for windy northern conditions, and logistical limitations. Chinese matchlocks were often of relatively crude local manufacture, with defective match cord or shot and a tendency to explode noted by Qi Jiguang that led their users to mistrust them.

I have read one source saying the Ming commonly used iron bullets rather than lead, with better armour penetration although more windage in firing.

Available resources focused on artillery, which includes everything down to rockets and very light guns and mortars. The small Crouching Tiger Cannon (hu cun pao) was tiny but very useful (see below).

Representing Chinese shot as all Arquebus with Light Spear in the front rank is consistent with FOGAM and in playtesting works well vs. Japanese if Poor. The range issues work properly facing teppō Musket*, the Japanese having the range and accuracy advantage but being outnumbered in dice (intimidating) at close range, prompting a desire to charge and gain the advantage starting in Impact. Historical tactics of long range fire and then close range fire to disrupt followed by a charge were fostered and worked. As mentioned with regard to archers, it also works dynamically better against horse archers than HW does.

Chinese infantry (Mixed Formations, Crossbow and Bow):

What a BG of either Crossbow or Bow represents may include a minority of the other type as well as troops with gunpowder weapons and other devices in some cases. It also includes one or more ranks of melee troops for steadiness and to form a front against enemy attacks. Ratios among BG types may therefore differ from actual troop ratios due to the varying proportions within units.

There was a historical Chinese preference for the crossbow, with both great range and penetration power, its primary limitation being the amount of time it took to load, draw, and fire. The Ming, however, preferred the bow, short bows for mounted combat and longer composite bows for infantry. In the Ming dynasty, the trend was a rising ratio of bows to crossbows, in part because firearms substituted for crossbow in some roles, but the actual mix of shooters and other troops in a particular army depended on what was available or could be begged or borrowed from elsewhere rather than the commander’s preference. Accordingly, a minimum of both types is required.

They liked to use fire arrows, particularly in siege and naval warfare. While some of these weapons were simply ordinary arrows wrapped with pitch or other inflammable materials, others contained explosive devices or gunpowder in small amounts. The most interesting of these designs was the rocket arrow. The rocket arrow was said to have great range and power, piercing through iron breastplates and hardwood planks, but was apparently almost impossible to aim, so usually released in massive intimidating swarms.

Front-rank Light Spear POA for archers is reasonable and provides continuity from the Ming FOGAM list. The alternative of HW front rank and Bow or Crossbow in the rear rank makes the shooting fairly weak in effect and may over-represent the close combat troops where the army also has close combat-only BGs. It also gives no Impact POA but does give a Melee POA, which is the wrong way around vs. Mongols and Manchus (won’t matter vs. Japanese).

Firearms battalions are wei (brigade) level formations with missile components consisting entirely of firearms troops (e.g., matchlocks plus traditional firearms such as 3-eyed guns). Front-rank Light Spear represents the close combat component. Arquebus of generally Poor grade represents troop quality, the quality and quantity of matchlocks and other firearms, and reduced effectiveness due to the proportion of non-missile troops. The “Veteran” firearms battalions represent the best formations in an army.

Side note: mixed formations and 3-eyed guns 1600s image link:

http://chinese-gun.freewebspace.com/photo.html

Southern coastal veterans:

Southern troops from Zhejiang had skill with firearms and were originally organized by Qi Jiguang in 1559 and trained in evolving tactics for fighting Japanese-style pirate opponents. Unlike northern troops, mostly cavalry, with experience against nomad horse archers, southerners were found effective in Korea, so China rotated in more southern troops during the Imjin War. They inspired imitation by the Koreans. The northerner/southerner rivalry was an ongoing feature where they fought together. Qi Jiguang’s experience with poorly made small arms exploding or misfiring prompted him to limit their numbers.

Mandarin Duck represents Qi Jiguang’s special formations both employed against the Wo-k’ou pirate swordsmen on the south-eastern coast and against the Mongol horse archers on the northern frontier. It is one of the Chinese mixed formations intended to coordinate different types to fend off dangerous melee attackers. These are classified as Spearmen with Pistol as their function, in game terms, was to maintain a tightly disciplined formation to deny their opponents the effective use of their superior swordsmanship and engage the enemy with fire at short-range and this provides the approximate effect. This is in contrast with the characteristic loose formation individually-oriented fighting style of Chinese troops.

Firearms were an integral part of the Mandarin Duck units, used at short range (the 3-eyed gun’s range was very short). Ultimately 2 firearms soldiers were added per squad in addition to the matchlockmen and light artillery at company and higher levels. Qi Jiguang was reluctant to increase the proportion of matchlocks due to the performance and hazards of the poor-quality Chinese weapons available. Qi’s war wagon units fielded light artillery on the wagons and a much greater proportion of firearms.

Cavalry gets an Impact POA against them in the open but the Spearmen get a POA against mounted in Impact and Melee.

Steady Spears neutralize Japanese Lancer Impact POA and Melee Swordsmen POA, which is the key intended effect against Wo-k'ou, Mongols, and Japanese with Swordsmen or no Melee POA. Spearmen 2 deep get Impact POA against foot unless protected pike/shot or Impact Foot. Works vs Manchu and Wo-k'ou. Late Japanese foot may have POA advantage in Impact, and POA neutral in Melee against Swordsmen (Samurai) and shallow Pike, which works.

Spearmen with front rank pistol (note Pistol (handgun) foot shoot 1 dice per 2 bases) seems the best representation of later Mandarin Duck in the south. In playtesting, having Pistol for each base made them too missile-heavy. Against the Mongols and in Korea, apart from the battle wagons, one rank of HW plus one rank of arquebus is an option, with the Koreans having a mixture of mixed formation BGs with Bow capability and those with Arquebus capability.

Artillery

As discussed under the Ming Tactical System section, Ming artillery was a continuum of weapons from man-portable devices to giant heavy guns, and continued to include non-gunpowder artillery in sieges. The used smoke and explosive grenades, as did the Koreans.

The Japanese were impressed by the Ming cannon as a reason to avoid pitched battle, which the Ming realized and exploited by adding more. Allied deployments found a good use for Korean archery on the wings and the heavier Ming guns in the center.

Use of cannon in suitable defiles was very effective, as at Chiksan 1597 in Korea.

The larger Ming field artillery pieces included the Portuguese-derived folangji (e.g., 1-2 meters long and firing a lead ball of up to 5cm diameter), which were often mounted on ships, and native models such as the Grand General Cannon (da jiangjun pao) or the Great Distance Cannon (wei yuan pao), These remained the core of the Chinese artillery well into the Qing era.

The Crouching Tiger Cannon (hu cun pao) was an important type that distinguished itself in Korea, used to great effect at the Battle of Pyongyang in 1593. They were about two feet long and thirty-three pounds in weight, able to fire a load of over one hundred (.43 ounce) pellets, like a smaller version of grapeshot. Man portable, it had two legs to elevate the barrel and was pegged to the ground before firing.

This and other light artillery was a key part of the Ming army and its firepower strategy. Artillery was typically distributed among the units to be engaged in close support, which is represented as regimental guns for missile troops in FOGR. These light artillery had an additional morale impact on northern horsemen, but in FOGR regimental artillery don’t have it as they are not included under either “firearms” or “artillery.”

Regimental Guns represent rockets and other light artillery used in quantity in front-line close support of the infantry, primarily at short range and in concentrated fire to bolster defence against enemy charges. Both the minimums and maximums for Light cannon and rocket launchers are reduced by half the number of Regimental Guns used in the army, rounded up.

The Heavy Artillery minimum reflects more large guns being taken on campaign later. There is no Heavy Artillery minimum since they were usually deployed in fixed positions for ambush, siege or defence rather tan in open field battles.

Portuguese or European-style cannon from 1621 allowed in lieu of heavy guns represents the few advanced Portuguese cannon (Hung Yi Da pao) obtained and during the reign of Tianqi from 1620. The 3 Portuguese guns purchased and used on the Manchu front in 1621 were “credited with beating off the enemy virtually unassisted.”

Gan Si Dui (Dare-die men), also translated as dare-to-die men, were tough shock troops picked, often ad hoc, for dangerous assignments. They were equipped with a mix of weapons including grenades, fire-lances, firearms, halberds, swords and other weapons suitable to the mission, which might include special operations on the battlefield (such as burning a critical garrisoned grain warehouse in Korea) or assaulting to breach enemy defences.

Southern tribal foot: Southern tribes (referred to as Miao) were considered martial peoples and valued as shock troops, primarily in the region but also used on the northern frontier and in Korea. They are limited to one BG if used in the same army as Mongol or Jurchen BGs or allies except that one BG is allowed in the Imjin War Korea Special Campaign.

Chinese or southern tribal skirmishers: This is a carry-over. The Qing used them. I am advised that to the extent these were used in field battles during the Ming period, they would be armed with bows or firearms.

Other Chinese wei-suo or militia represents the worst of the regulars as well as local militia, rebels, etc. The Ming discouraged local militia outside the Wei-suo system, but local armies.

Qi Jiguang’s battle wagons appear to have been used in practice only in the Chichou region near Beijing after he assumed command and re-equipped the troops. These carried 2 light artillery each and other firearms, and were each manned by a crew of 20 fighting in and adjoining the wagons. Mandarin Duck infantry and battle wagons are assumed to survive in the Chichou army for the 3 years after his transfer in 1582 (i.e., until the year of his retirement). This means they may be used during the renewed Mongol war of 1582 until at least 1585. Although it is reasonable that forces from Chichou may have been included among those mustered from across China for the Korean campaigns of the 1590s, their methods are assumed to have reverted due to lack of support or maintenance as there is no mention of the battle wagons.

Screens and other portable barriers adjoining wagons are purchased by up to one eligible BG of Mandarin Duck infantry (and other infantry if all Mandarin Duck infantry have them) per BG of battle wagons and can only be deployed in contact with battle wagons by the front rank of a file of troops that is in side or corner contact with friendly battle wagons. They must be enough to cover the frontage of the BG when deployed in 2 ranks. Portable defences were used as part of a wagon laager against barbarian cavalry, providing friendly cavalry with shelter inside until ready to sortie.

Imjin War Special Campaign: This represents both the 1592-93 and 1597-98 campaigns. The composition of the expeditionary forces changed greatly. The best troops were temporarily occupied suppressing the Ordos Rebellion of Pubei in Ningxia while larger armies were struggling with Yang’s rebellion in the south.

The first force sent to Korea was raised in Liaodong in August 1592 to send a message to the Japanese “bandits” and drive them out if practicable. It was 5000 men, mostly cavalry and spear/dao men, under Vice Commander of Liaodong Zhao Chengxun. Overconfident, he marched into Pyongyang, was ambushed, and the remaining troops retreated north.

Li Rusong’s army of 36,000 troops or more (total force estimates up to 50,000) arrived in January 1593. It was strong in cavalry, non-missile infantry and artillery. It included 3,000 southerners from Zhejiang trained in Qi’s methods, skilled with firearms and experienced against Wo-k’ou pirates, as well as some mixed foot with bowmen. Turnbull stresses that the Japanese had arquebus and muskets but Li Rusong’s force had no matchlocks. Turnbull sometimes overgeneralizes, and I believe that there were simply few matchlocks (perhaps only among the southerners) and the army was light on shot as opposed to artillery. The army had over 2000 artillery pieces on pack animals or military carts, which were distributed evenly among his units before the attack on Pyongyang. The army was mostly mercenaries drawn as usual from outcasts, bandits and poor peasants, rewarded for headcount turned in (to the misfortune of civilians) and needing discipline. Commissioner Song considered over 20,000 of these 36,000 to be battleworthy, the rest not, and was concerned that too many were cavalry unsuited to the campaign.

After the assault on Pyongyang and an accidental meeting engagement in foggy, muddy, and rolling terrain north of Seoul at Pyokje, the Ming were impressed with Japanese musketry and the Japanese by Ming artillery. Both sides thereafter pursued a more circumspect approach.

The Chinese, with close political oversight by critical censors, generally advanced with caution, their goal to force the Japanese out rather than punish and destroy them as the Koreans wished. The Japanese were content to have the Allies bloody themselves in sieges and assaults, which also offered opportunities for sharp Japanese counter-strokes that could drive back the allied attackers, or even rout them with great slaughter as at Sachon in 1598.

The infantry armour upgrade represents use of stronger iron armour and shields in the later Imjin War to counter heavy Japanese musketry in assaults.

Captured Japanese and deserters were put into Ming service. Their teppō skills were useful in spreading firearms knowledge and fighting in close terrain such as in the southwest against Yang’s rebellion through its end in 1599-1600. This is a single historical flavour BG from 1598 to approx 160X?, either Medium Foot or Light Foot, Arquebus, possibly Armoured.

Chinese Rebels. China faced numerous revolts as usual, some of which were substantial wars, and the Shun, operating from a base in Shaanxi 1634-1647, led by Li Zicheng proclaimed the Shun Dynasty and in 1644 seized Beijing without great difficulty (to be beaten shortly thereafter in a hard-fought battle against the Manchu, who put Wu Sangui’s turncoat Ming army in the front of the fight). In addition to Li’s core of regular troops, they included numerous recruits motivated by liberation from Ming oppression. They reportedly had more cavalry than their Imperial opponents as well as equivalent weaponry. They were at their greatest strength from 1636-1644.

Rebel armies usually coalesced around a core of army troops and can be generally covered by allowing use of the normal list excluding special campaign variations, excluding troops specifically from a different region (e.g., southern infantry, northern (Mongol or Jurchen) cavalry), and including compulsory irregulars ranging from bandits, mercenaries, and enthusiastic volunteers to peasant levies.

Ming Claimants 1644-1662. Ming claimants in the south would not have access to northern barbarian horse.

Three Feudatories 1662-1683. A dangerous southern revolt against the Manchu that approached success in the 1670s. A “colour unit” for this period is

Portuguese mercenaries (date? just during the rebellion itself 1673-81?) are rated as Salvo for their reliance upon an initial volley and a fierce onset. I have not researched the southern campaigns or the Elephants found in the DBR list.

Ming Chinese List Ideas and Info

Moderators: nikgaukroger, rbodleyscott, Slitherine Core, FOGR Design

Misc

PLAYTESTING Ming vs. Japanese:

Playtesting of the draft list at something over 700 points per side focused on the battle line interactions of Ming vs. several varieties of my draft Japanese types. It went very well, with a mixed line of Poor Shot and Crossbow and some Spear/dao men vs. Japanese infantry fitting well for both sides. The Ming player said the high volume of fire although reduced effect feels right for Ming, and though the centra line crumbled over time it was a harder contest than the Japanese hoped. Average would be excessive for Ming - the Firearms battalions were dangerous by virtue of their numerous shooting dice which could see a good run and because they ignored the superior armour of the Japanese in melee. Quality tipped the balance - a Superior Samurai contingent had to be thrown in to force it in time (IF/SW in this case, the other Samurai was Speamen). Meanwhile the Ming horse on one wing routed Japanese cavalry and sandwiched a yumi infantry BG. On the other wing the Southern coastal veterans were grinding forward, the other Japanese cavalry (2 BGs are excessive numbers of horse for this battle, but there for testing) tried to keep its distance from their weak but hazardous shooting until time to charge in between the uneven terrain areas. The rocket launchers caused problems for a pinned Japanese BG and knocked off a base before the Japanese could charge the guns and beat the spear/dao men behind.

Except for special assault units, Ming infantry in this period is Average to Poor, both mercenaries of varying quality and the better hereditary (wei-suo) troops. The worst wei-suo foot and conscripts are Mobs. The conclusion was that a lot of Poor quality troops with enhancements accurately reflects the army.

Ming FC, 3 TCs

Guard Cavalry, 1x4 Cv/Armoured/Superior/Bow/Swordsmen

Mercenary Cavalry, 2x4 Cv/Armoured/Average/Bow/Swordsmen

Mercenary Cavalry, 1x6 Cv/Unarmoured/Poor/Bow/Swordsmen

Mongol Cavalry, 2x4 Cv/Unarmoured/Average/Bow/Swordsmen

Mongol Cavalry, 1x6 LH/Unarmoured/Average/Bow/Swordsmen

Spear/Dao-men, 2x6 MF/Unarmoured/Poor/HvyWpn

Seperate Crossbow, 1x8 MF/Unarmoured/Poor/Crossbow w/LtSp front reggun

Firearms, 2x8 MF/Unarmoured/Poor/Arquebus w/LtSp frontLtS reggun

Rocket Launchers, 2 LtArt/Avg/

Gansidui, 1x4 MF/Armoured/Superior/Impact Foot/Swordwmen

Southern coastal veterans, 3x8 MF/Unarmoured/Average/Pistol/Spearmen

Weapons, Armour and Appearance Misc Notes

Chinese swords of the Ming period had their origins in central Asian sabres. Ming infantry swordsmen usually carried a goose-quill or willow leaf sabre. The former was straighter and more suitable for thrusting than the latter, which had a deep curve and was primarily a slashing weapon. Sabres were often used in combination with a shield by special fighting squads.

Yellow silk banners might have the characters Tai Ming = Great Brightness.

Ming armour: Good mail for Imperial bodyguards. Brigandine used by mounted and some foot. Field troops usually quilted cotton armour, some stuffed with soft material, some with iron strips for reinforcement. 1587 161

Red coats over studded leather or quilted cotton armor which might have metal studs or strips; shields of bamboo, wood or iron; and often helms.

Late Korean war reference to the colorful red-uniformed Zhejiang troops of Luo Shangzi. DHST 337

Large shields also used when facing enemy archers or in sieges. By 1597 the Chinese had developed stronger and more bulletproof armour which saw some use in Korea, as well as iron shields. DHST 249

Equipment was inconsistent, usually supplied by relatively crude village manufacture. Quality issues and lack of standardization characterized military supply and was a significant problem. 1587, 162

Transition from FOGAM List:

This has Ming infantry as loose order, individual fighters, with no Heavy Foot other than the Anti-Cavalry Heavy Weapons troops appearing in the FOGAM lists, consistent with prior lists, including Gush allowing 16 halberds to upgrade to HI. In this period the zhanmadao long anti-cavalry sword was replaced by the changdao, General Qi Ji-guang’s modification of the Japanese nodachi he faced in battle. This was widely used for the remainder of the Ming dynasty, and standard equipment for Qi’s musketeers. In game terms a FOGAM-like Heavy Foot anti-cavalry unit is probably unnecessary at this scale.

FOGAM lets horse archers gain a POA against Medium Foot in open ground, representing the difficulties that prompted the Ming to adopt various expedients to protect themselves against mounted assaults. These are represented by Light Spear in FOGAM and in FOGR, and is more important in FOGR since there is no Impact support shooting in FOGR. Mechanically, Regimental Guns help even out the loss of support shooting dice in Impact.

Playtesting of the draft list at something over 700 points per side focused on the battle line interactions of Ming vs. several varieties of my draft Japanese types. It went very well, with a mixed line of Poor Shot and Crossbow and some Spear/dao men vs. Japanese infantry fitting well for both sides. The Ming player said the high volume of fire although reduced effect feels right for Ming, and though the centra line crumbled over time it was a harder contest than the Japanese hoped. Average would be excessive for Ming - the Firearms battalions were dangerous by virtue of their numerous shooting dice which could see a good run and because they ignored the superior armour of the Japanese in melee. Quality tipped the balance - a Superior Samurai contingent had to be thrown in to force it in time (IF/SW in this case, the other Samurai was Speamen). Meanwhile the Ming horse on one wing routed Japanese cavalry and sandwiched a yumi infantry BG. On the other wing the Southern coastal veterans were grinding forward, the other Japanese cavalry (2 BGs are excessive numbers of horse for this battle, but there for testing) tried to keep its distance from their weak but hazardous shooting until time to charge in between the uneven terrain areas. The rocket launchers caused problems for a pinned Japanese BG and knocked off a base before the Japanese could charge the guns and beat the spear/dao men behind.

Except for special assault units, Ming infantry in this period is Average to Poor, both mercenaries of varying quality and the better hereditary (wei-suo) troops. The worst wei-suo foot and conscripts are Mobs. The conclusion was that a lot of Poor quality troops with enhancements accurately reflects the army.

Ming FC, 3 TCs

Guard Cavalry, 1x4 Cv/Armoured/Superior/Bow/Swordsmen

Mercenary Cavalry, 2x4 Cv/Armoured/Average/Bow/Swordsmen

Mercenary Cavalry, 1x6 Cv/Unarmoured/Poor/Bow/Swordsmen

Mongol Cavalry, 2x4 Cv/Unarmoured/Average/Bow/Swordsmen

Mongol Cavalry, 1x6 LH/Unarmoured/Average/Bow/Swordsmen

Spear/Dao-men, 2x6 MF/Unarmoured/Poor/HvyWpn

Seperate Crossbow, 1x8 MF/Unarmoured/Poor/Crossbow w/LtSp front reggun

Firearms, 2x8 MF/Unarmoured/Poor/Arquebus w/LtSp frontLtS reggun

Rocket Launchers, 2 LtArt/Avg/

Gansidui, 1x4 MF/Armoured/Superior/Impact Foot/Swordwmen

Southern coastal veterans, 3x8 MF/Unarmoured/Average/Pistol/Spearmen

Weapons, Armour and Appearance Misc Notes

Chinese swords of the Ming period had their origins in central Asian sabres. Ming infantry swordsmen usually carried a goose-quill or willow leaf sabre. The former was straighter and more suitable for thrusting than the latter, which had a deep curve and was primarily a slashing weapon. Sabres were often used in combination with a shield by special fighting squads.

Yellow silk banners might have the characters Tai Ming = Great Brightness.

Ming armour: Good mail for Imperial bodyguards. Brigandine used by mounted and some foot. Field troops usually quilted cotton armour, some stuffed with soft material, some with iron strips for reinforcement. 1587 161

Red coats over studded leather or quilted cotton armor which might have metal studs or strips; shields of bamboo, wood or iron; and often helms.

Late Korean war reference to the colorful red-uniformed Zhejiang troops of Luo Shangzi. DHST 337

Large shields also used when facing enemy archers or in sieges. By 1597 the Chinese had developed stronger and more bulletproof armour which saw some use in Korea, as well as iron shields. DHST 249

Equipment was inconsistent, usually supplied by relatively crude village manufacture. Quality issues and lack of standardization characterized military supply and was a significant problem. 1587, 162

Transition from FOGAM List:

This has Ming infantry as loose order, individual fighters, with no Heavy Foot other than the Anti-Cavalry Heavy Weapons troops appearing in the FOGAM lists, consistent with prior lists, including Gush allowing 16 halberds to upgrade to HI. In this period the zhanmadao long anti-cavalry sword was replaced by the changdao, General Qi Ji-guang’s modification of the Japanese nodachi he faced in battle. This was widely used for the remainder of the Ming dynasty, and standard equipment for Qi’s musketeers. In game terms a FOGAM-like Heavy Foot anti-cavalry unit is probably unnecessary at this scale.

FOGAM lets horse archers gain a POA against Medium Foot in open ground, representing the difficulties that prompted the Ming to adopt various expedients to protect themselves against mounted assaults. These are represented by Light Spear in FOGAM and in FOGR, and is more important in FOGR since there is no Impact support shooting in FOGR. Mechanically, Regimental Guns help even out the loss of support shooting dice in Impact.

Reconsidering the special Imjin campaign breakdown. In September 1598, one of the three Allied armies was Liu Ting's, 26,000 Ming, "the bulk of them cavalry units and contingents of ethnic fighters from Burma and other exotic locales along the periphery of the Middle Kingdom" about half of which he took in the advance on the coastal forts, to be joined by 10,000 Koreans.

The change would be that Southern tribal foot should not be restricted. Individual allied contingents are probably still too small to represent, and Burmese in particular would not have Elephants.

The change would be that Southern tribal foot should not be restricted. Individual allied contingents are probably still too small to represent, and Burmese in particular would not have Elephants.